Fragments of

- Solomon K.

- Dec 13, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 15, 2025

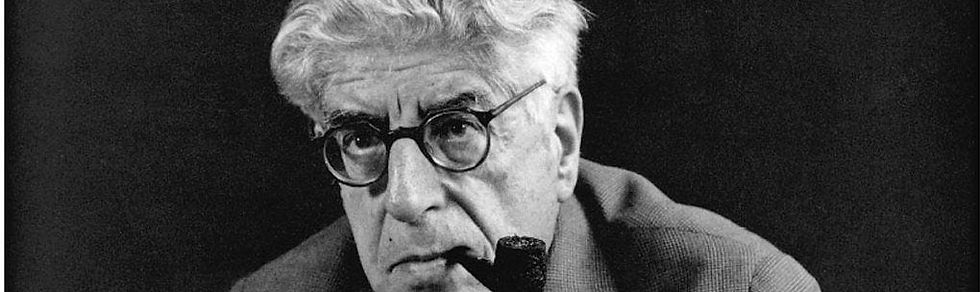

This is a great opportunity for a word on the Theologico-Political Fragment of Walter Benjamin, an article on the Messiah, by the legendary intellectual.

It is opportune because Taubes writing on Paul references it particularly! saying that the nihilism of Paul is that nihilism of Benjamin’s Fragment...

Benjamin says, according to Taubes, that only the Messiah completes all of history. Nothing inside history stands alone separately - all things are measured in relation to Messiah. Only he fulfills history and gives it meaning.

This is what Paul is saying essentially, in Romans, giving the history of salvation, it is messianic history. Everything leads and builds up to salvation.

Methodical Pause

According to Taubes, the young Benjamin, writing in 1921 apparently, after the end of the Great War, attributed a nihilism of sorts to the world and all its political history - a position attributed to Paul, as Paul felt towards the Roman empire and the form of the world itself, the cosmos - is on the verge of transformation.

Who was Benjamin polemicizing against? And Paul? These are questions that Taubes asks, because in order to understand a text, one must understand that the act of writing is political, it is a dispute with someone, or something, and only after answering that question, then we can begin to interpret a text...

History as Profanity

The simple understanding of Benjamin’s text is what Paul said of the history of salvation in Romans, as Taubes showed us, a nihilism of sorts, as the ways of the world and all their political institutions will change.

All political things in this world have zero significance: They are all profane and meaningless, including theocracy as a political system, is meaningless.

Benjamin says that history is a process, but the messianic, or utopia, is not part of that process, but the end of it - the process, history, is profane.

Messianism by definition is external to the profane political historical process.

Hopeful Striving by Nature

Benjamin references Ernst Bloch in the Spirit of Utopia (written not long before the Fragment after the Great War) for taking apart the idea that there is political significance in theocracy, as such an ideal religious government system might have religious significance, but there is no significance or meaning in politics.

But mankind possesses a hopeful consciousness that strives for ideals and fulfillment - this is real, an existential disposition, which can be expressed through religion and more... it makes us creative and it makes us operate for constructive transformation.

Do not confuse that striving with political objectives, for by doing so one reduces and empties its profoundness and effectiveness.

Impossible Accessiblity

That is why Benjamin says that the Divine Kingdom, or the messianic kingdom, is not part of history - it is not the telos, the peak, the fulifllement... but the end, it is beyond the process of history, it is not accessible.

These are forces in opposite directions. The pursuit of happiness and other ideals through politics, versus the pursuit of the metaphysical objective.

But, he explains, there is a paradox. Although the utility of political action, or activisim within history, which is profane and will pass as well, and cannot lead to the messianic essence, there is a paraxical principle by which the profane pursuit inadvertently induces divine redemption...

How so? Pushing the political leads to its passing. The pursuit of political ideals induces the collapse of political systems, which precedes transformation.

Such an attitude is nihilistic - the assumption that all things are void of significance, and that they are bound to collapse.

Comparing Notes

The Fragment reminds me of a few things we reflected upon in the series here, working through principles of messianism over generations through traditions.

Note he says something about striving for happiness. As if history is hopeful and working towards a better world and happiness… but happiness is the opposite direction from the messianic. Why is that? Because this world will fall apart, it will utterly change, before the messianic redemptive transformation.

In our notes, particularly in the rabbinic literature, we reviewed many principles in the context of messianism. One was activism, as to induce or hasten the coming of the Messiah or the messianic age.

The opposite principle was determinism, in that there is nothing you can do that will change anything, it comes when it comes, when G-d ordains it. Yet another voice synthesized these options...

Benjamin's approach is deterministic. The efforts of mankind to bring about the messianic are absurd, pointless. Activism, the efforts to achieve happiness, peace, or justice through politics, will lead to nothing. However, paradoxically, such meaningless activism in the end might induce the messianic.

I am also reminded of Scholem’s categorization of kinds of messianism, one of which is catastrophic. Truly the classic messianic idea was eschatological, apocalyptic, catastrophical, and perhaps more deterministic - following catastrophic events, which precede cosmological transformation. In that sense, Benjamin was right to describe messianism as deterministic and catastrophic.

Post Ideology

The Fragment was surely inspired by the events of the Great War and Bolshevik revolution, and what was considered by many socialists as disappointment of structures and of ideology itself.

The world surely felt as if it went through a collapse, nationalism and socialism and all, the Hegelian program - the idea of progress - all felt like absurd ideas.

In that context, Benjamin plays on the ideas and concepts of messianism to say that ideological and idealistic movements, political enterprises, the pursuit of happiness - all are in vain.

But, as so many millions of people and kingdoms did exactly that, they missed their objectives, and in their failure, through monumental catastrophe, maybe ground is broken for an era that is the opposite reality of things?

Has Walter Benjamin said something about the traditions of messianism throughout Jewish history? No. Rather, he has taken terms and phrases of messianism, and his philosophical ideas and critique, and made messianism into a philosophical theme.

History is not progress - progress is a lie. Instead of history as a construct written by the victors, a counter messianic history refutes these constructs. There is no clear history, only fragments.

Messianism is thus also a position in regards to structured history, opposing it, and seeking justice to those who were oppressed by it.

It is the opposite of Hegelian historical logic and essentially theologizing the political structures, it is the opposite of their totality logic.

Benjamin will later develop this position and call it weak messianic power - a drive that he calls messianism, but a subtle and subversive version of messianism, but power nonetheless... An expression of the profound deep factor in our souls that is hopeful and seeks justice.

Theological-Political Fragment (English)

First the Messiah completes all historical occurrence, whose relation to the messianic he himself first redeems, completes and creates. Therefore nothing historical can intend to refer to the messianic from itself out of itself. For this reason, the kingdom of God is not the telos of the historical dynamic; it can not be set towards a goal. Historically seen, it is not a goal but an end. Thus the order of the profane cannot be built on the idea of the kingdom of God; therefore theocracy has no political, but only a religious significance. To have repudiated the political meaning of theocracy with all intensity is the greatest service of Bloch’s Spirit of Utopia.

The order of the profane has to be established on the idea of happiness. The relation of this order to the messianic is one of the essential elements in the teachings of historical philosophy. It is the precondition of a mystical conception of history, whose problem permits itself to be represented in an image. If one directional arrow marks the goal in which the dynamic of the profane takes effect and another the direction of messianic intensity, then clearly the striving for happiness of free humanity strives away from that messianic direction. But just as a force is capable, through its direction, of promoting another in the opposite direction, so too is the profane order of the profane in the coming of the messianic kingdom. The profane, therefore, is not a category of the kingdom but a category – that is, one of the most appropriate ones – of its most quiet nearing. For in happiness everything earthly strives for its decline and only in happiness is the decline determined to find it. While clearly the unmediated messianic intensity of the heart, of the inner, individual person, passes through unhappiness, in the sense of suffering. To the spiritual restitutio in integrum, which introduces immortality, corresponds a worldliness that ushers in the eternity of the decline and the rhythm of this eternal passing-away, passing-away in its totality – worldliness passing-away in its spatial but also temporal totality – the rhythm of messianic nature is happiness. For messianic is nature from its eternal and total transience.

To strive for this, even for those stages of humanity which are nature, is the task of world politics whose method is called nihilism.

Comments