Kafka's Judgment

- Solomon K.

- Dec 16, 2025

- 9 min read

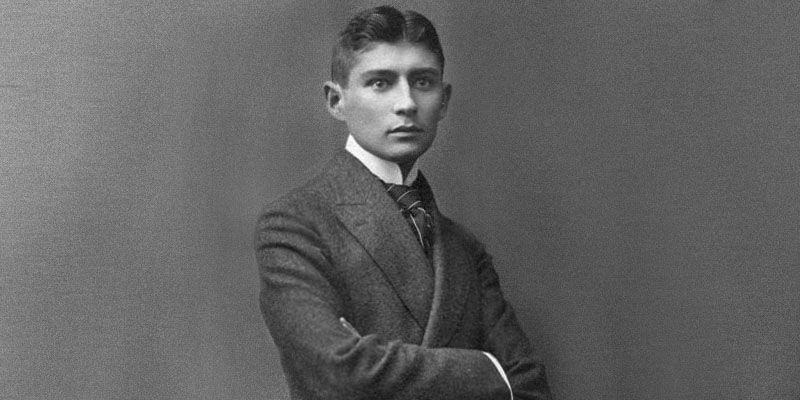

The mysterious dark secular Jew from Prague, but culturally German, lived from 1883 to 1924, and died at the young age of 40 by tuberculosis. He was a failed writer in his time, but posthumously world famous, a legendary literary figure.

Around 1917-1918 he wrote a series of aphorisms in his notebooks, including this one about the Messiah:

The Messiah will come as soon as the most unbridled individualism of faith becomes possible--when there is no one to destroy this possibility and no one to suffer its destruction; hence the graves will open themselves. This, perhaps, is Christian doctrine too, applying as much to the actual presentation of the example to be emulated, which is an individualistic example, as to the symbolic presentation of the resurrection of the Mediator in the single individual.

The Messiah will come only when he will not be necessary, he will only come after his arrival, he will not come on the last day, rather on the very last.

There are two parts, but often only the second is quoted by intellectuals or quasi-intellectuals. At face value, the first part emphasizes the individualism of the messianist, not the Messiah. As an individual, the messianist does everything, and then, when the invidiualism is fully manifested, the Messiah will come.

The second part, especially when interpreted on its own, sounds much more ironic, a much sharper aphorism, as a single sentence...

It is discussed also by Walter Benjamin and Gershom Scholem, no less, in writings published by Scholem years after Benjamin’s death.

Kindred Spirits

Scholem was interested in metaphysics. Benjamin was also somewhat into metaphysics, but mainly in ‘materialism’ - he was part of the Frankfurt school, a circle of marxist / socialist intellectuals who criticized ideology.

Scholem hated Benjamin's other friends in the socialist intellectual circles. He tried to make a Zionist out of Benjamin and failed, but seemed to succeed in encouraging Benjamin's interest in metaphysics.

Scholem dedicated the famous published lecture series - ‘Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism’ to Benjamin - “friend of a lifetime whose genius united the insight of the Metaphysician, the interpretive power of the Critic and the erudition of the Scholar.”

That was in 1940, right after Benjamin died by suicide while fleeing the Nazis in Spain, after fleeing France, after fleeing Germany. Scholem became responsible for Benjamin’s legacy of writing and publishing rights.

They discussed all sorts of things related - including messianism and Kafka, whom they outlived, observed, and venerated as some sort of oracle, who felt and expressed the deepest meanings of human existence.

Kafka was a clever writer who was interested in Judaism and Jewish mysticism, but the expression of these can only be enigmatic in his writings.

While Scholem believed that Kafka can only be interpreted as pointing to theological things, Benjamin saw in the theological reading but one way to interpret Kafka, not exclusively. For example there was also the bureaucratic reading, the alienated powerless man against the authorities and such.

Both agreed that ‘Before the Law’ (Vor dem Gesetz), the parable inside the novel ‘The Trial’ (Der Prozess), says it all. It tells of a man from the countryside who is denied entry to the Law by the gatekeeper, for years, until he dies...

Existence in a Nutshell

Scholem, scholar of Jewish mysticism, posited that one must read Kafka in order to learn Kabbalah with understanding! And in order to understand Kafka one must read the biblical book of Job - because Job is all about dealing with judgments that you cannot by any means perceive let alone influence.

Scholem viewed halacha, the commandments, the Torah, as that which defines Judaism, but - in and of itself, the halacha has no value.

As a religion, the revelation of Torah is necessary, but then it has no meaning beyond that. Mt. Sinai, the giving/receiving of Torah, was Judaism's great revelation, and is necessary as such, but we cannot perceive it, we cannot perceive value in the commandments themselves, of halacha itself. That, according to Scholem, is Judaism, is Kafka: it gives the religion value, but has no value in and of itself.

That is how Kafka for Scholem is Jewish theology - one stands before judgment, on the basis of the Law that is absurd, that is nonsensical, because by it you are not justified, you cannot actually obtain justice or be redeemed. And G-d is the punishing judge, while there is no redemption that is accessible: He demands what cannot be performed and then condemns you for it. By intuition, somehow, Kafka understood the essence of Judaism and Jewish theology, with only minimal knowledge of the sources.

Benjamin’s Kafka is different. He puts his ideas through Kafka (as Scholem does with his ideas), somewhere between the Marxist / materialists and the Hebrew theological intellectuals in regards to Kafka. Benjamin thought that both interpretations were legitimate here, or both part of the parable's essence...

On the one hand, it is man in the face of cruel arbitrary political abuse of power, with feelings of alienation, a disposition of being persecuted by authorities and elites, having no say, control, nor justice - being on the other side of those who were victorious and powerful in history who dictated the narrative and shaped the structure of culture and society, who used and lied to helpless common people.

On the other hand, the theological reading spoke to Benjamin... That materialist critical interpretation is not sufficient to bear this text - these must be more truth to Kafka's writings. Standing before the Law as the daunting bureaucratic system must also be standing before diving judgement, the Torah, G-d.

Materialism does not contain all the religious and spiritual essence. Religion was used, as ideology, to control the masses, but there is more to religion.

Benjamin was skeptical whether the materialists can achieve their objective of an ideal society, a d even if this would happen, hypothetically, still, the concept of redemption and religious philosophical truth, is beyond obtainable objectives of ideals for society.

Materialism operates within history, it is activism, it is the medium of the profane, while Messianism is that which is not part of history, it is the opposite of profane, it is religious, it is not something one attains, it is not the object of any activism.

If we circle back to the the meaning of Kafka’s famous aphorism above, of messianic arrival on the day after redemption, Benjamin would read his position into those words, that messianism is the category that is beyond and set apart from activism, history, and even a fixed society. Messianic redemption is not any ideological movement nor political enterprise, but somehow redeeming the past, or its memory, fixing all the suffering that was... Not salvation but repentance.

Remembering

This was supposed to be about Kafka but felt so far it was more about Benjamin and Scholem, which is true because, as they themselves agree, Kafka was so enigmatic and clever and left so much open for interpretation. He wrote and died, and then was published and has been under interpretation ever since.

Kafka was indeed interested in Judaism as an adult, including Hebrew and Zionism and Folklore and Mysticism. The fact that he writes about the Messiah is already evidence that such things have entered his mind and pen.

Kafka intensely read Kierkegaard, the great religious existentialist, and shares such principles in all his writings, for example, anxiety and guilt and paradox and irony. And Kierkegaard was a great influence on many modern Jewish theological thinkers, who would be inclined to the theological reading of Kafka.

Specifically in the passage above, Kafka mentions Christianity and individualism directly, which presumably has everything to do with Kierkegaard. It makes sense that this passage first of all is meant to express a clever ironic thought…

But what is interesting as pupils of messianism, in relation to the traditional concepts, is that there are questions throughout the ages and texts whether the Messiah will come and craft that messianic age, or will he just appear at the end of it, when all things have already been completed.

The messianic era could be that which precedes his arrival, or the event of his arrival, or that which follows in some ideal or restored state of the world. In that sense, Kafka through this aphorism is poking at substantial ideas and feelings.

Kafka’s work in general, the notion of is later called Kafkaesque, a state of being in anxiety, alienation, almost schizophrenia, is relatable in the agonizing waiting for the Messiah, who is supposed to come, but then does not, always coming, living in between.

Take for example the tale of the Messiah who was discovered at the pool of lepers in Rome who says 'today I will come' and then, whe he did not come that day, Elijah explains - "today IF you heed my voice…" quoting the 95th Psalm. It all feels surreal, ambiguous, very messianic, and very Kafkaesque.

What is the Law

Finally, I must comment that the famous parable, the ultimate text - Vor dem Gesetz, translated as ‘Before the Law’, takes me back to Taubes and Paul.

Paul writes, particularly in Romans, particularly chapters 7-8, of the ‘Law’. There, Nomos, is not translatable directly as Torah, rather, it is ambiguous, it could be Torah, or the Roman concept of Law, or both, or sometimes this sometimes that.

Reading Paul and trying to understand what exactly he is referring to is quite Kafkaesque, frankly. But Paul is describing a situation where his adherents feel like the hero of Kafka before the Law - they feel condemned, guilty, helpless, perhaps anxious… And Paul gives them the messianic solution, a new law, to free them from those feelings and that disposition.

Anyhow, Kafka reminds me of Paul in that aspect, with the obsessive conscious engagement with this Law concept. And I do feel that Scholem and Benjamin interpret Kafka’s Law in somewhat of a traditional Christian Pauline manner, which wouldn’t be too much of a stretch, as they were both raised and educated in German Lutheran society.

Scholem’s Law, of Kafka and of Judaism, is the Law of Paul, without the Messiah...

Vor dem Gesetz, English

Before the law sits a gatekeeper. To this gatekeeper comes a man from the country who asks to gain entry into the law. But the gatekeeper says that he cannot grant him entry at the moment. The man thinks about it and then asks if he will be allowed to come in later on. “It is possible,” says the gatekeeper, “but not now.” At the moment the gate to the law stands open, as always, and the gatekeeper walks to the side, so the man bends over in order to see through the gate into the inside. When the gatekeeper notices that, he laughs and says: “If it tempts you so much, try it in spite of my prohibition. But take note: I am powerful. And I am only the most lowly gatekeeper. But from room to room stand gatekeepers, each more powerful than the other. I can’t endure even one glimpse of the third.”

The man from the country has not expected such difficulties: the law should always be accessible for everyone, he thinks, but as he now looks more closely at the gatekeeper in his fur coat, at his large pointed nose and his long, thin, black Tartar’s beard, he decides that it would be better to wait until he gets permission to go inside. The gatekeeper gives him a stool and allows him to sit down at the side in front of the gate. There he sits for days and years. He makes many attempts to be let in, and he wears the gatekeeper out with his requests. The gatekeeper often interrogates him briefly, questioning him about his homeland and many other things, but they are indifferent questions, the kind great men put, and at the end he always tells him once more that he cannot let him inside yet. The man, who has equipped himself with many things for his journey, spends everything, no matter how valuable, to win over the gatekeeper. The latter takes it all but, as he does so, says, “I am taking this only so that you do not think you have failed to do anything.” During the many years the man observes the gatekeeper almost continuously. He forgets the other gatekeepers, and this one seems to him the only obstacle for entry into the law. He curses the unlucky circumstance, in the first years thoughtlessly and out loud, later, as he grows old, he still mumbles to himself. He becomes childish and, since in the long years studying the gatekeeper he has come to know the fleas in his fur collar, he even asks the fleas to help him persuade the gatekeeper.

Finally his eyesight grows weak, and he does not know whether things are really darker around him or whether his eyes are merely deceiving him. But he recognizes now in the darkness an illumination which breaks inextinguishably out of the gateway to the law. Now he no longer has much time to live. Before his death he gathers in his head all his experiences of the entire time up into one question which he has not yet put to the gatekeeper. He waves to him, since he can no longer lift up his stiffening body.

The gatekeeper has to bend way down to him, for the great difference has changed things to the disadvantage of the man. “What do you still want to know, then?” asks the gatekeeper. “You are insatiable.” “Everyone strives after the law,” says the man, “so how is that in these many years no one except me has requested entry?” The gatekeeper sees that the man is already dying and, in order to reach his diminishing sense of hearing, he shouts at him, “Here no one else can gain entry, since this entrance was assigned only to you. I’m going now to close it.

Comments