Spiritualistic Movement

- Solomon K.

- Oct 5, 2025

- 5 min read

In a few words, to introduce us contextually to Hasidut, for our purposes here exploring messianism… Hasidut could be translated as piety, or kindness perhaps. The word today often means adherence, or a Hasid is an adherent of some ideology or movement or group, etc., and of course - a member of a particular Hasidic group or court.

Hasidism could be described as a movement, or religious movement or a spiritual movement. Or a trend. Or a phenomenon. Here it is not approached as an organized movement or institutionalized school at all. Rather, here it is considered a cluster of trends typically associated as Hasidut. That is to say, not one phenomenon but a bunch of loose phenomena bits.

It Begins, Some Context

We begin in the mid-18th century in Eastern Europe, where millions of Jews lived, in areas today mostly Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, and northern Romania. These areas were connected somehow during the Polish empire where Jews had partial autonomy, what was called the Council of Four Lands.

During that era, Jews were traumatized notably by the Chmelnitzky uprisings of Ukrainian nationalism, slaughtering tens of thousands of Jews - which also had to do with the societal structure: it was a revolt against Poland, and Polish nobility, who were owning the lands, using Jews often to handle the tax collection and manage the Ukrainian peasants.

Then there was the Sabbatian movement which wreaked chaos. Besides the religious aspects, many Jews were persecuted, and otherwise lost their stature, so there was even more poverty, and those within the Jewish community who were still connected to the political and economic institutions versus those who were basically peasants themselves, poor and working. On a religious level, the religious institutions became stronger after the Sabbatian debacle, these were those who were opposed to Sabbatianism and maintained their stature, and were more conservative, rationalistic, elitist one could say.

In the above context there were traveling special individuals who brought omens and theurgical kabbalistic divine name practices, to cause healing and other little miracles and wonders.

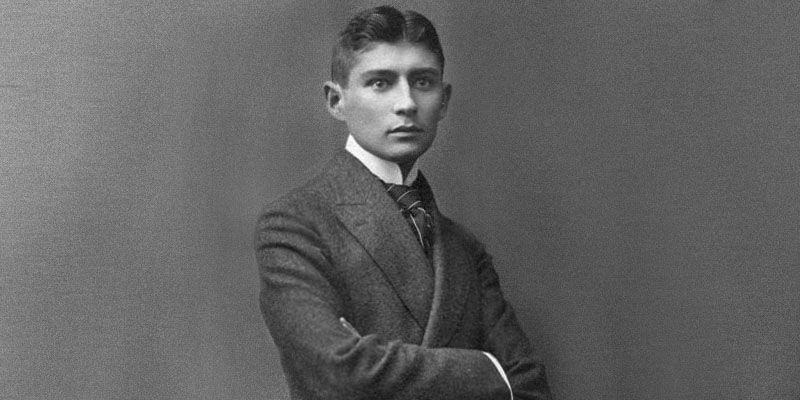

They were called “individuals of good namesake”, ba’al shem tov. And now we begin with one rabbi, Yisrael son of Eliezer, the Ba’al Shem Tov. (aka the besht)

Start-up to Institutionalization

In a context following the Sabbatian chaos, one could say, that was very conservative towards popular messianism and kabbalah, a seed survived, one could say, of messianism and spiritualistic isms, in the hearts and minds of the people, and through the Hasidic ‘movement’.

What followed was this traveling special spiritual man somehow started a following, people started following him, these were his new disciples, as he would pray and preach and isolate himself and fast and sing, and what not.

With time, all sorts of people joined this loose group, which became known as Hasidism. They did share some general associations and common principles of faith and religious life.

Historians speak of different phases - the first early period, the core of the original Besht following, with much charisma, anti-institutionalism, popular spirituality, spontaneity.

His many disciples, mostly from the rabbinical elite circles actually. They wrote, whereas the Besht did not write, for example, and organized, and spread the ideas and growing models of spiritual religious life. But with time, especially when they passed, sects formed.

Then you had eventually separate institutions of Hasidic association, and then particular institutions for particular Hasidic sects. They were called “courts”, and the leaders were called “tsaddiq” - not ba’al shem tov, and the leadership was passed on through the bloodline mostly, like a dynasty.

So we speak of Hasidic dynasties today. Quite far from the original Besht.

A Bit of Actual Content

We mentioned the Ba’al Shem Tov style roots - personal charisma, popularistic and spiritualistic and kabbalistic, the opposite of elite and rationalistic Judaism.

When Hasidut became institutionalized over history, lots of these ideas and principles remained in some shape or form.

The Besht preached, he did sermons, a lot of which were through stories, creative descriptions.

He taught Zoharic and Lurianic Kabbalah. Some of the essential principles are simply Lurianic Zoharic Kabbalistic ones - the Divine is in every thing, there is a root of good in all things, and in the evil things deep down at the root there is good and divine - so one must not deny or flee but face and dive deep to understand such roots in the suffering and sinfulness, etc.

Even the exile, being in the Diaspora, is understood in this manner. Thus everything about life is religious - the field in which they labor to raise the sparks of divine holiness within the other side.

Until today, on that last point, many Hasidic followers see their life outside of Israel as spiritually significant, in the field of the other side, extracting holiness from those places.

So universal divinity, stories and sermons, dancing and strong prayers - a spiritualistic lifestyle, clinging mystically - all these are part and parcel of the Hasidic worldview (besides Halacha and such), Jewish kabbalistic spiritualism.

Back to the Subject Matter

We haven’t said much until now about messianism. Well, we did say in previous posts that Lurianic Kabbalah with the sparks and everything were historically perceived as messianic.

Actually there was a big argument between Israeli scholars whether Hasidic trends were messianic or not - and we consider this big discussion quite outdated and irrelevant. Because we don’t see Hasidism as one movement, but rather a bunch of different trends and ideas.

So the question is not whether Hasidism at large is or was messianic but rather we would ask - what are the messianic elements here and there among associated Hasidic trends and texts?

Well, one interesting view from that big argument was interesting - besides the view that said yes it was messianic, vs. the view that said it is or was not messianic, the view of Gershom Scholem was that it was and was not messianic.

He called it neutralized messianism, and by that he meant that they utilized some of the messianic ideas and concepts but reduced the fervor, the zeal, the sting, the activism.

Why that is interesting, is not because I think that view was accurate, but it contextualizes Hasidism as a post-Sabbatian phenomenon, in other words, there was so much going on contextually as reactions towards Hasidism, and the content of Hasidism, that was impacted by Sabbatianism.

More of that to come! I decided to really simplify the presentation of messianism in Hasidism from the 3 famous and influential individuals who were messianic - the Ba’al Shem Tov himself, his great grandson Rebbe Nachman of Breslev, and finally - Chabad / Menachem Mendel Schneorson - the Lubavitcher rebbe.

Comments